By Yuhan Yang, Rodney Weber and Bill Simpson

We often think about air quality in terms of how much particulate matter is floating around in the air we breathe. This makes sense as health studies consistently link breathing in particles to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.

The real danger, however, might not be how much overall particulate matter is in the air. Instead, it might be how toxic the particles are.

Fairbanks residents spend a lot of time indoors during the winter, raising the importance of indoor air quality. Research conducted in Fairbanks in 2022 as part of the Fairbanks Winter Air study sheds light on the quality of indoor air during the winter months. The study was conducted in a typical home in the Shannon Park area. This house, much like many in the community, kept its windows shut tight against the cold.

Pollution chemists spent six weeks measuring air pollutants inside and outside this house. To figure out how the particles can affect health, they dissolved the particles in water and measured their ability to produce harmful chemicals. In this way, they can measure the toxicity of the particles in addition to their concentration in the air. Because the chemicals in particles from different sources have different toxicity, the toxicity per particle varies.

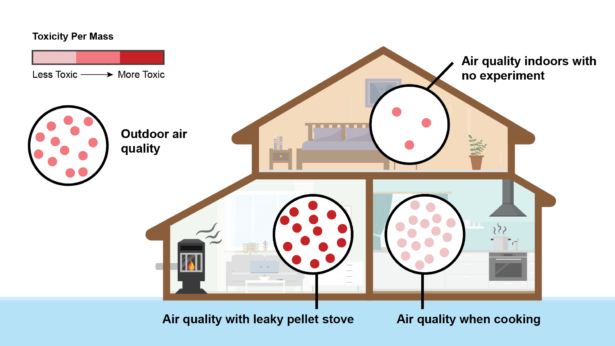

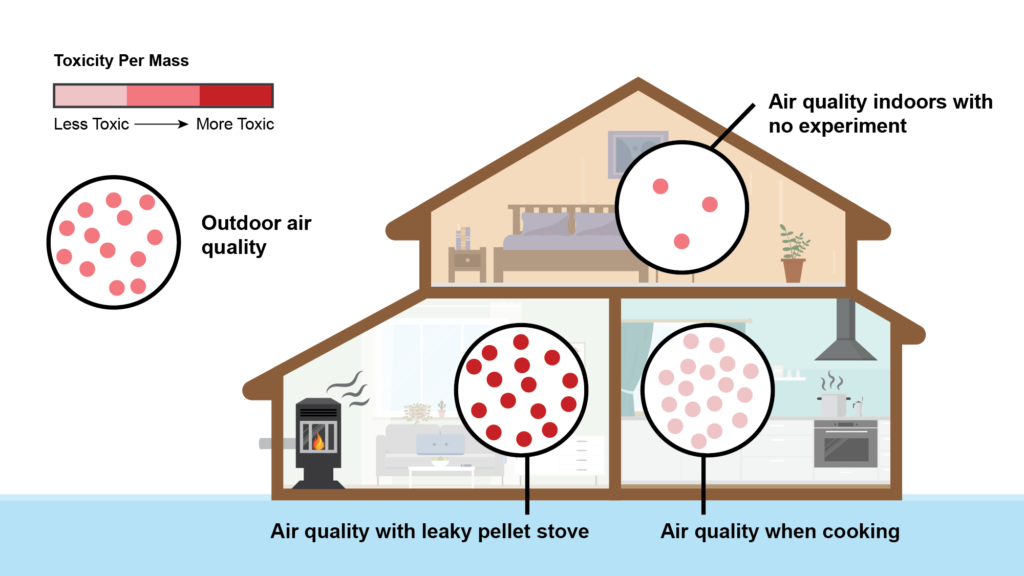

One important result of this study was discovering that outdoor particles that did find their way indoors not only decreased in concentration by about 80% but also reduced in their toxicity. With the significant changes in temperature and humidity between outside and indoor conditions typical during Fairbanks winters, some toxic components of particulate matter evaporated as they came indoors. This means indoor environments provide some protection from harmful outdoor pollutants.

Caption: Particulate matter (PM) measurements outside and inside a house. The color of the particles represents a chemical measurement of effective toxicity per particle. Image credit: Molly Putman, UAF GI Design Services.

While being indoors may shield residents from the impact of outdoor pollutants, activities inside the home can create their own particulate matter with different levels of toxicity. This study measured the particulate levels and associated toxicity of several indoor activities, including heating with a pellet stove, cooking and burning incense.

The Shannon Park home’s pellet stove was plagued by a small exhaust leak that emitted wood-smoke particles into the house, elevating indoor particulate concentrations to levels comparable to outdoor pollution. These indoor particles proved to be nearly one and a half times more toxic per particle than their outdoor counterparts.

In contrast, while cooking emitted a significant mass of particulates, especially during activities like frying, their toxicity per particle was notably lower by about half compared with outdoor pollution. This assumes, of course, that you don’t burn your food. In fact, cooking particles were even less toxic per particle than the background indoor particulate matter. This suggests that although cooking can temporarily spike indoor particle levels, the overall health effects are likely reduced compared with breathing the same amount of outdoor or pellet-exhaust particles.

What does this mean for Fairbanks residents?

First of all, sealing our homes against the cold helps to keep out most of the outdoor pollution. But perhaps the most important takeaway is this: The amount of particles alone doesn’t tell the full story of indoor air quality. The type of emission and the amount and toxicity of the particles also play significant roles in assessing health risks. By understanding these effects, we can take meaningful steps to ensure the air we breathe indoors is as clean and safe as possible.

These findings, which were recently published in a scientific publication, “Indoor–Outdoor Oxidative Potential of PM2.5 in Wintertime Fairbanks, Alaska: Impact of Air Infiltration and Indoor Activities,” highlight the impact of diverse sources contributing to indoor air quality.

This Community Perspective is part of a series of articles on air quality research performed as a part of the University of Alaska Fairbanks-led Fairbanks Winter Air Study (https://fairair.community.uaf.edu). The authors are Yuhan Yang and Rodney Weber from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Bill Simpson from UAF.